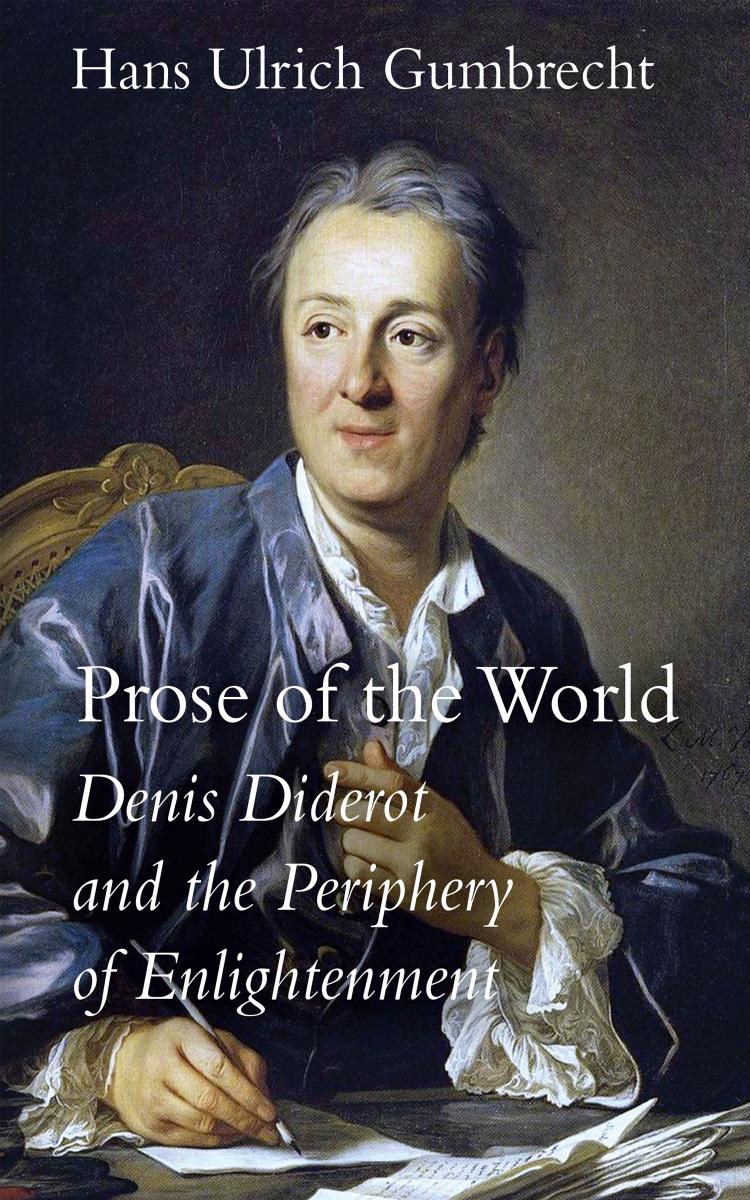

Prose of the World: Denis Diderot and the Periphery of Enlightenment by Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht

Author:Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht [Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich]

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

ISBN: 9781503615250

Google: tA-pzQEACAAJ

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2021-11-15T23:48:50.141812+00:00

6

âQUELS TABLEAUX!â

Acts of Judgment and the Singularity of Phenomena in Les salons

DURING THE LATER MONTHS of 1767, the small group of aristocrats in Eastern and Central Europe subscribed to Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimmâs Correspondance littéraire, philosophique et critique had an opportunity to read what Denis Diderot thought about his own appearance and about its rendition in a number of portraits, among them a large format by his older friend, the court painter Michel van Loo, that was exhibited in the current Salon of contemporary painting and sculpture at the Louvre.1 Nine times between 1759 and 1781 (with three interruptions), Diderot covered these biannual events for the Correspondance littéraire, in different tones and at different levels of precision, and all commentators agree that his writing about art reached its peak in 1765 and in 1767. By then, instead of analyzing pictures and sculptures in the order they appeared on the walls and in some open spaces of the Louvre, he had developed an approach of comparing, discussing, and evaluating the works of different artists in separate, individual clusters.2

Within one such cluster, Diderotâs reaction to van Looâs painting, announced in the Salon catalogue as â8. Le Portrait M. Diderot,â stands out because, beginning with a triple opening reference to himself as the object of representation, as a friend of the artist, and as a thinker, it allows us to sense a will to independence from the genre-specific objectivity claims, aesthetic values, and discursive traditions that had long determined art criticism: âMOI. I like Michel myself, but I like the truth even moreâ (288).3 In the words following the pronoun âMOI,â Diderot refers to Aristotleâs famous statement that he was âa friend of Plato but even more so a friend of truthâ; âMOIâ refers to his likeness in van Looâs work; but the pronoun also connects with the grammatical subject of the following sentence and can thus give more weight to its content as a personal principle (truth is a greater value than friendship); finally, these words do come together in a syntactical form that often articulates acts of judgment. But as we may assume that prioritizing truth over friendship must have been a moral principle for Diderotâs readers, rather than the result of a moral judgment, we will read these words as announcing, in the friendliest possible way, a not entirely positive aesthetic judgment of van Looâs painting.

A series of quick, direct judgments referring to the relationship between the painting and Diderotâs self-image follows in the next sentences, where friendly gestures of approval are repeatedly undercut by critical remarks:

Itâs quite like me, and he can say to anyone who doesnât recognize it, like the gardener in the comic opera: âThatâs because heâs never seen me without my wig.â Itâs very much alive; thatâs his gentleness, and his liveliness; but too young, the head too small, pretty like a woman, ogling, smiling, simpering, mincing, pouting; nothing of the sober colouring of the Cardinal de Choiseul.4

While Diderot sees a certain degree of resemblance

Download

Prose of the World: Denis Diderot and the Periphery of Enlightenment by Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht.pdf

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7132)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6950)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5419)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5375)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5202)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5187)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4317)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4197)

Never by Ken Follett(3963)

Goodbye Paradise(3813)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3778)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3403)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3088)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3077)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3039)

Will by Will Smith(2930)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2928)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2850)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2740)